The Civil War took the lives of more Americans than all the other United States conflicts combined, from the American Revolution through Vietnam. Amazingly, more soldiers succumbed to disease, such as measles and dysentery, than died from the awful wounds caused by grape, cannister, and rifled musket minie balls. Being a White or a Black soldier in the conflict between the North and the South was no glamorous adventure; it was horror of the worst magnitude.

Mississippi played a pivotal role in the war. The second state to secede from the Union, its secession resolution, like those of the other southern states, clearly stated that defense of slavery was its reason for leaving the Union. With a population of 791,000 people, Mississippi's enslaved people outnumbered White people 437,000 to 354,000. Slavery, therefore, seemed to be an absolute necessity for the state's White citizens. White soldiers from Mississippi reflected the state's position on slavery, but they fought for a variety of other reasons, too. Some joined the military to defend home and hearth, while others saw the conflict in broader sectional terms. The soldiers' motivation was generally more personal than it was ideological.

Mississippi's location along the strategic Mississippi River made the state a scene of a number of major battles inside its boundaries or nearby. The names Vicksburg, Jackson, Raymond, Port Gibson, Corinth, Iuka, and Meridian resonate in Civil War historical writing as do nearby Shiloh, New Orleans, Memphis, and Port Hudson. Black and White Mississippians not only sent soldiers to war, they frequently experienced hard fighting first hand.

Mississippi soldiers

White and Black soldiers from Mississippi contributed to both the Union and Confederate war efforts, fighting within the state and as far away as the battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. Around 80,000 White men from Mississippi fought in the Confederate Army; some 500 White Mississippians fought for the Union. More than 17,000 enslaved Black Mississippians and freedmen fought for the Union.

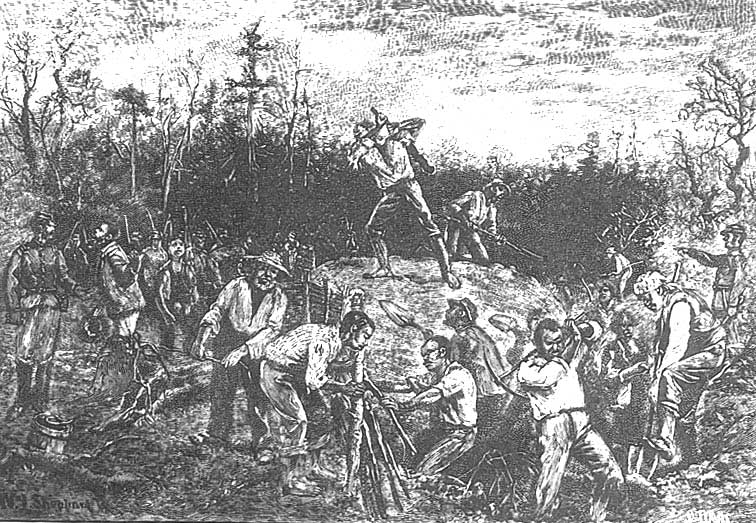

A large but undetermined number of enslaved persons served as body servants to White Confederate officers and soldiers, built fortifications, and did other manual labor for the Confederate Army. The thought of a Black man carrying a rifle was a horror to most White Mississippians, and the state resisted the enlistment of those who were enslaved even after the Confederate Congress authorized the policy near the end of the war in March 1865.

Information on the Black Mississippian's role in the Civil War military is limited. In recent years, the Civil War Conservation Corps, a voluntary group at the National Archives in Washington, D. C., has organized all the United States Colored Troops files housed there. The filming of these documents, including material on Mississippi, will begin in 2001 and microfilm should become available for public use soon after. Historians have already produced major books on these “colored troops,” as they were then known, thus providing insight into the Black soldiers from the Magnolia State.

Not surprisingly, more data is available on the White Mississippi fighting man than on the Black one. The typical Confederate soldier from the Magnolia State was very similar to the average Civil War soldier, whether Union or Confederate. Thus, most generalizations about all Civil War fighting men apply to those from Mississippi as well. Most Civil War soldiers were young men, eighteen to thirty years of age, but some were boys and old men who carried rifles. Most came from rural areas, had little education, and had never been far from home. Fighting in the great war, despite its horrors, was the greatest adventure of their lives.

Historians have been able to write important books on Johnny Reb and Billy Yank, as they were called, because these soldiers kept diaries and wrote letters. They also preserved their writings. Probably more personal historical data is available on the common Civil War White soldier than about participants of any other war in American history. Because so much material exists on these fighting men, it is impossible to discuss here every aspect of soldiers' lives or even to present anything but a tiny sampling of the letters and diary entries they wrote. These selected writings and this commentary allow the reader to gain an insight into the minds and experiences of the soldiers, though that insight is limited. Perhaps the sampling, although limited, will encourage readers to probe more deeply.

The bibliography that accompanies this essay contains a list of books that investigate in depth the experiences of Black and White soldiers. These books, part of the excellent historical writing about the Civil War, provide detailed and analytical insights. Numerous histories of military units, biographies of military leaders, and published soldiers' diaries and correspondence, also contain excellent information on these troops.

State and local history journals, like the Journal of Mississippi History, have, over the years, regularly printed soldiers' diaries and letters. Popular Civil War magazines like Civil War Times Illustrated, America's Civil War, and North and South, to cite several, also frequently include this kind of material in their issues.

Letters and diaries

What kind of information is available? As the writings included with this essay show, anyone interested in learning about Civil War soldiers will have no problem finding pertinent material. An inquirer can come to understand the variety of motivations for enlistment and the procedures used to incorporate the new recruit into the military. Camp life and the devastating incidence of disease and resulting death graphically appear in soldiers' letters and diaries, as do details about the shortages of food, clothing, and mail from home.

Soldiers talked about the scarcity of newspapers, the incompetence or brilliance of Confederate leaders, the girls they left behind, the prisoner of war camps that sometimes held them, the songs they composed, the foraging and damage they caused, and the weather that seemed either too hot or too cold, or too wet or too dry. In letters and diaries, soldiers mentioned the body enslaved that some soldiers brought with them and the attempts they made to stay in touch with family and friends. There is also evidence of the hostility Confederate soldiers and civilians had for runaway enslaved people and African Americans in Union uniform.

Most graphic of all are the battle accounts. Not always patiently, Mississippi soldiers withstood long marches under normally terrible weather and road conditions. They grew hungry and thirsty and so tired that sometimes they felt as though they were marching in their sleep. In their writings, they talked about the horror of being in battle, of shooting at other human beings, of seeing someone desert in a panic, or of feeling the overarching fear that caused them to run away themselves.

All too often, they were wounded and went through the horror of a stay in a hospital, trying to regain health under the most unsanitary conditions. Viewing the carnage that remained on the battlefield after the firing stopped usually proved heartrending, and soldiers freely described their participation in battle as frightening, not glorious.

Over and over again in their letters and diaries, soldiers talked about wanting the war to end so they could go home. But, almost as often, they pledged to remain until a true peace arrived. Rumors repeatedly appeared in soldiers' letters and diaries, including those from Mississippi. A rumor might be something as simple as gossip about when the column would stop for the evening or its destination for the next day. Or, rumors might involve how another Confederate army fared on a distant battle field and what that meant for the unit of the writer. Or, a rumor might concern the death or wounding of a friend or the dismissal of a famous general. Sometimes, rumors came from the writer's hometown about a close relative's health or the love life of an acquaintance.

As the war drew to a close, many Mississippi Confederates despaired when they realized that the war would be lost. The secession resolution that had sent them to war had pledged to defend slavery. Now, slavery and the way of life it represented appeared lost. Yet, the war, the soldiers who fought in it, and the resolution that began it would continue to affect the Magnolia State into the new millennium.

The link below takes you to selected soldiers' letters, diary entries, and official war era documents. This material gives an insight into military life during the war and indicates the richness of documentation available at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, the Old Courthouse Museum in Vicksburg, similar repositories throughout the state and nation, and in a wide variety of books and articles.

We have edited this prose as little as possible so that the soldiers' words, misspelled and ungrammatical as they could sometimes be, tell their own story. We have, however, silently introduced paragraphing and punctuation to make their comments more understandable.

Documents

- A Declaration Of The Immediate Causes Which Induce And Justify The Secession Of The State Of Mississippi From The Federal Union

- State Law, Early In The War, To Control Slaves

- Army Order To Control Slaves

- Young Men Want Parents' Permission To Enlist In Army

- Soldier's Struggle To Get News

- High Prices For Clothes

- Battle Of Shiloh

- Soldier Worn Out But So Is His Slave

- Difficult Times But He Will Continue

- Where Are The Letters While He Is Ungloriously Fighting?

- Soldier Song

- No Letters From The Girls

- Marching Through Mississippi

- On The Way To Gettysburg, Both Sides Think They'll Win

- With Vicksburg Gone, Confederacy Might As Well Quit

- “The Great Gallantry Of The Negro Troops At Milliken's Bend [Vicksburg Campaign]”

- Confederate Treatment Of A Black Union Soldier

- Despite Troubles, War Must Go On

- Hardest Time Ever

- Captured And Feeling Melancholy In A Prison Camp

- Wounded In Battle

- Healing A Wound In Prison Hospitals

- Letter To A Wife On Death Of Her Husband

- Burial Of A Dead Soldier

- The Confederacy Is Lost

John Marszalek, Ph.D., is retired William L. Giles distinguished professor of history, Mississippi State University, and executive director and managing editor, The Ulysses S. Grant Association.

Clay Williams is director of the Old Capitol Museum, Jackson, Mississippi.

Bibliography

Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland (eds.) Freedom's Soldiers, The Black Military Experience in the Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland (eds.) Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series 2 The Black Military Experience. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Bettersworth, John K. Mississippi: The People and Politics of a Cotton State in Wartime, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1943.

Bettersworth, John K. and James W. Silver, eds. Mississippi in the Confederacy. Jackson: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1961.

Current, Richard Nelson. Lincoln's Loyalists, Union Soldiers from the Confederacy. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle, The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: The Free Press, 1990.

McPherson, James M. For Cause and Comrades, Why Men Fought in the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Redkey, Edwin S. (ed.) A Grand Army of Black Men, Letters from African-American Soldiers in the Union Army, 1861-1865.New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Robertson, James I. Jr., Soldiers Blue and Gray. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1988.

Weaver, C. P. (ed.) Thank God My Regiment An African One, The Civil War Diary of Colonel Nathan W. Daniels. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998.

Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Life of Johnny Reb, The Common Soldier of the Confederacy. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943.