Definitions for Women's Suffrage Amendment

In the 20th century, Mississippi legislators were twice called upon to act on two constitutional amendments that had major implications for American women. The first for their consideration was the woman suffrage amendment which was ratified in 1920 and became the Nineteenth Amendment. Second was the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) submitted to the states in 1972, but left unratified when the deadline expired in 1982. Mississippi approved neither of the amendments.

Both of the amendments provoked heated debates. Because the text of each amendment was quite brief and unspecific — the Nineteenth Amendment declared that the vote could not be denied on the basis of sex, while the ERA stated that legal equality should not be denied on account of sex — no one knew precisely what the amendments' actual impact would be. Therefore, both supporters and opponents read into them their own hopes and fears regarding the future of women and society.

This article, however, considers the state's response to the woman suffrage amendment.

Woman suffrage movement begins

The woman suffrage movement in America began in 1848, an offshoot of the anti-slavery movement. A separate women's rights movement emerged after women were left out at the time the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments extended the vote to African-American men. This decision was bitterly protested by the famous suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. While many White people in the South did not think the newly freed African Americans should vote at all, national suffrage leaders resented the fact that they received the vote before women.

In the 1870s suffragists sought the right to vote through an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court as well as through a proposed Sixteenth Amendment that would give women the vote. All efforts failed. National suffrage leaders reluctantly concluded that they would have to launch a grassroots campaign in each state to obtain state suffrage amendments. Once there were enough congressmen from woman suffrage states, they thought, a federal suffrage amendment would be approved by Congress and the amendment would be ratified by three fourths of the states.

NAWSA

By 1890, national leaders, united in a large suffrage organization called the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), realized that to achieve all this they would have to “bring in the South.” They were all too aware, however, that this might be hard to do. Many White southerners were hostile to the movement because it was an outgrowth of the antebellum movement to end slavery. They opposed it also because of regional pride in women remaining in their traditional role as “southern ladies” — which meant staying outside of politics except to encourage men to rule wisely for their sakes. Yet, a growing number of women in the South were eager to have the vote, both to improve the legal, educational, and employment opportunities for women and to promote reforms — especially those that would benefit women and children. But they were getting nowhere.

Then Mississippi attracted the attention of the nation and accidentally affected the course of America's woman suffrage movement when delegates to the 1890 Mississippi Constitutional Convention seriously considered giving the vote to women. They were responding to the suggestion of suffrage advocate and former anti-slavery activist Henry Blackwell of Massachusetts. Blackwell suggested that through giving the vote to women, White southerners might regain control of southern politics without taking the vote away from Black men and therefore getting into trouble with Congress. The proposal died in committee by just one vote. National suffrage leaders concluded that since one of the most conservative states in the nation had given serious consideration to enfranchising women in order to restore White supremacy in politics, suffrage leaders might use the race issue to persuade the South to lead the way for woman suffrage. White suffrage leaders seemed desperate to find an argument to persuade politicians to adopt woman suffrage, and therefore were willing to “play the race card” to get the vote for themselves in a time when most southerners wanted neither Black men nor Black women to vote.

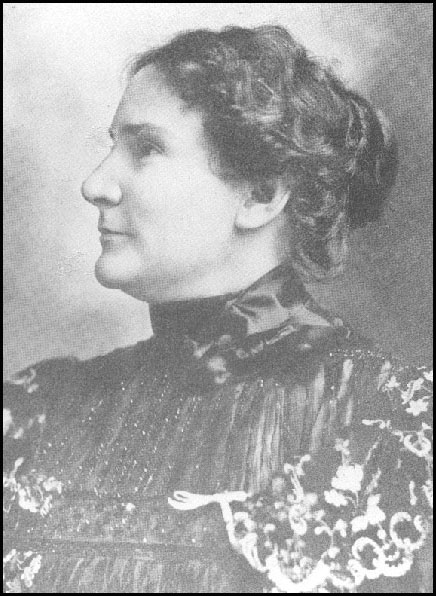

Nellie Nugent Somerville

National leaders spent a good deal of time and money in the South in the 1890s. However, other southern states followed Mississippi's lead in adopting literacy tests, poll taxes, and other means of disfranchising Black men rather than enfranchising women, and neither Congress nor the Supreme Court acted to stop them. So this southern strategy died — but not before the national leaders sent organizers into Mississippi to get a suffrage movement started in this seemingly very promising state.

Nellie Nugent Somerville of Greenville, Mississippi, was already active in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, a national organization that had endorsed woman suffrage, and she came to their aid. Somerville was annoyed that the national organizers burst into the state without first conferring with Mississippi women, but once they were here she did not want to see them fail. She accepted the presidency of the Mississippi Woman Suffrage Association, lending the social and political reputation of her family plus her own considerable organizing skills to this movement.

The suffragists worked very hard for several years speaking, writing, and distributing literature, and trying to gain support from the press, lawyers, politicians, and ministers. But by the early 1900s, they had nearly given up. At the same time, national leaders were giving up on the idea that the South would lead the way.

Belle Kearney

In 1906, Belle Kearney of Madison County, Mississippi, a professional speaker who was often traveling outside the state, returned to Mississippi long enough to bring the woman suffrage association back to life — but she soon left it once again in the hands of Somerville. Gradually the suffragists built support. They established chapters in many towns, made speeches, sponsored booths at the state fair, and won over a few newspaper editors and political leaders including governors James K. Vardaman and Edmund Noel. They never won over the vast majority of state legislators. Highly conscious of the strong feelings against suffrage in the state and region, they designed literature and tactics to “make friends without making enemies” as Somerville put it. They wrote most of their own brochures and leaflets, aware, as suffragist Lily Wilkinson Thompson said, that “an ounce of Mississippi was worth a pound of Massachusetts.”

The women working for woman suffrage were White, middle- and upperclass women, and were radical, for their culture, only on the issue of woman suffrage. The state's chapters of the temperance union and the Daughters of the American Revolution never came out as a group in favor of woman suffrage, but many of their members actively promoted woman suffrage in the state. The Mississippi Federation of Women's Clubs endorsed it in 1917.

The suffragists were always treated with respect by the leading politicians, often meeting in the Governor's Mansion or the capitol. One year they set up their headquarters in the lobby of the capitol during the legislative session. They were “ladies” and they always dressed and behaved in a ladylike fashion. From the very beginning in 1898, Somerville had warned Mississippi suffragists that, “the public, and especially the editorial public, will be quick to see and use against us any mistakes that may be made. An unpleasant aggressiveness will doubtless be expected from us. Let us endeavor to disappoint such expectations.”

The National Woman's Party, a group of more militant suffragists who had demonstrated for suffrage in front of the White House and been thrown in jail for it, sent representatives to Mississippi in 1917. They organized a conference in Vicksburg and established a chapter, but it was not very active. Most suffragists in the state considered militant tactics unattractive and counterproductive. Politicians like Senator John Sharp Williams of Mississippi denounced the Woman's Party's demonstrations outside the White House as “asinine bonfire performances.” Instead, Mississippi suffragists attempted to participate in activities that would attract support for their cause. For example, during World War I, they made their patriotism clear through active support of home front defense activities.

The suffragists were well aware that many Mississippians believed states should have the right to decide what state voting requirements should be. Since many of them shared that belief, they made it clear that they preferred to receive the vote by a decision of their own state rather than by federal action. Sharing the racial views of most men of their race, they also stated that they wanted the vote exactly on the terms that Mississippi men had it at the time — in other words with provisions that excluded African Americans.

House reacts to suffrage amendment

Yet all of the suffragists' caution and conservatism did not convince most legislators to support woman suffrage. The one major state suffrage campaign, in 1914, failed. Representative N.A. Mott of Yazoo County introduced the suffrage resolution which was referred to the House Committee on the Constitution. The committee recommended against it. But when a minority on the committee requested a public hearing, one was scheduled. Nellie Somerville, Belle Kearney, Lily Thompson, Pauline Orr (a professor at the Industrial School for Girls, now Mississippi University for Women), and others spoke for the amendment. Speaker H.M. Quin of Hinds County gave up the chair to speak in favor of the amendment. But other legislators insisted that woman suffrage was not in the best interests of Mississippi women; that people in their home districts did not want it; that if the amendment were submitted to voters they would “bury it beyond resurrection;” and that women should remain, as Joe Owen of Union, Mississippi, said, “queen of the home and hearthstone.” Owen also stated, “I am absolutely, inherently, fundamentally, first, last, and all the time opposed to woman suffrage.” The House rejected the resolution by a vote of 42 to 80.

By 1915 many Mississippi suffragists had concluded that the state was unlikely to extend suffrage to women on its own. They believed they would only get the vote in their lifetimes if a federal woman suffrage amendment was added to the U. S. Constitution. Belle Kearney and Nellie Nugent Somerville joined the growing number of southern women who tried to convince fellow southerners that woman suffrage by federal amendment was not a threat to the South.

The national campaign’s final push

Somerville accepted a vice presidency in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She was highly influential in convincing southern suffrage leaders to support the proposed amendment — even though a former friend and ally, New Orleans suffrage leader Kate Gordon, a strong state's rights suffragist, opposed woman suffrage by federal action and urged all southern women to oppose it.

NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt and other national suffrage leaders organized the final push for Congressional approval of the amendment. They urged suffragists from “hopeless” states like Mississippi not to start campaigns for state suffrage amendments since they would probably fail and it would make the federal amendment seem unpopular. Suffragists in some southern states were furious about this. But Somerville and other Mississippi suffragists, apparently agreeing with Catt’s strategy, followed her lead without protest. When Senator Earl Richardson of Neshoba County introduced a state suffrage amendment in 1918, the suffragists were surprised — especially when it received a favorable committee report and a tie vote of 21 for and 21 against. Requiring a two thirds majority, however, the measure still failed.

The state’s rights issue

When Congress sent the woman suffrage amendment to the states for ratification in June 1919, the state's rights issue was an additional and powerful obstacle to its success. Many southern politicians feared that if the woman suffrage amendment was approved, the federal government would then enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments requiring the states to allow Black men to vote. In 1919, many still regarded these amendments that had been passed by Congress and approved by the states after the Civil War as unfair since the states were required to ratify them before being readmitted to the Union. Therefore, they insisted that ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment would suggest that the South now approved of these post-Civil War amendments and was willing for them to be enforced. To reject the federal woman suffrage amendment, on the other hand, would send a strong message to Congress about southern determination to resist interference in state’s rights to decide who could vote and who could not.

Suffragists supported, suffragists opposed

Nevertheless, Mississippi suffragists formed a Ratification Committee and in December opened a headquarters in Jackson, the state capital. By then the amendment had been ratified by 22 states. The suffragists were aided by national Democratic Party leaders, including President Woodrow Wilson, who thought American women were on the verge of gaining the vote and were eager to win their favor. President Wilson pressured state leaders to ratify for the sake of the Democratic Party. Out-going Governor Theodore G. Bilbo got on board, saying, “woe to the man who raises his voice or hand against the onward sweep of this great cause.” Incoming Governor Lee Russell also supported ratification, denying that the amendment infringed on state’s rights. The suffragists also enjoyed the support of many state newspapers including the Jackson Daily News, which emphasized woman suffrage was inevitable and would not endanger white supremacy, writing: “the door of hope is forever barred to Sambo, insofar as suffrage is concerned.”

On the other hand, The Clarion-Ledger took the lead in opposing ratification, even hiring state’s rights suffragist Kate Gordon to come to Mississippi and speak against the federal amendment. And for the first time, Mississippi anti-suffragists decided to bring in out-of-state representatives of the Southern Women's League for the Rejection of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. But there was so little fear about ratification that no permanent anti-suffrage organization was formed in the state.

Indeed, a poll of the Mississippi House of Representatives by the Jackson Daily News indicated that there was not a “ghost of a show for ratification.” And in late January, Representative William A. Winter of Grenada (father of the William Winter who later became governor of Mississippi) introduced a resolution to reject the amendment as “unwarranted, unnecessary, and dangerous interference” with state's rights. It was the same language found in rejection resolutions in other southern states.

House of Representatives rejects amendment

Taking the suffragists by surprise, the House rushed to vote, and amidst cheers and laughter the representatives approved the rejection resolution 106 to 25. At that point many suffragists gave up. In February, the Mississippi Senate refused to ratify by a vote of 14 to 29. The Clarion-Ledger congratulated them, stating that “the vile old thing (the Susan B. Anthony Amendment) is as dead as its author, the old advocate of social equality and intermarriage of the races, and Mississippi will never be annoyed with it again.”

To everyone's surprise, however, it was not over. Near the end of the legislative session, when the amendment had been passed by 35 states and only one more was needed, some state senators felt the state must ratify for the sake of the national Democratic Party. On the motion of William Beauregard Roberts of Rosedale, the House bill to reject was recalled, amended to read ratify, and passed when Lieutenant Governor H. H. Casteel broke a tie in favor of the bill. Astonishing the nation, the Mississippi Senate had ratified!

But the House reaction was swift and negative. Walter Sillers of Bolivar insisted that woman suffrage was here and that “a vote against this amendment is a vote against the Democratic Party,” but to no avail. As many legislators cheered him on, R.H. Watts of Rankin County insisted “he would rather die and go to hell” than vote for it, and the House voted it down by 90 to 23.

Amendment added to U.S. Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment was at last added to the Constitution, however, in August 1920 after Tennessee became the 36th and final state to ratify. It had taken almost 75 years for suffragists to achieve this victory.

The final indication of Mississippi's negative response to the Nineteenth Amendment was that the state was one of only two in the nation that did not allow women to vote in the November 1920 election. Instead, an all-male electorate voted on a state constitutional amendment for woman suffrage that received more yes than no votes, but not the majority of all votes cast. Therefore, the amendment failed. Suffragists had not bothered to campaign for it since they were enfranchised by national law and the state law would not matter. Nevertheless, it was still very disappointing to them that Mississippi, their home state, had not approved woman suffrage. Yet, a mere two years later, in one of the many ironies in Mississippi history, the state's two leading suffragists, Somerville and Kearney, were elected to the state legislature.

By the 1970s, when Mississippi was debating the proposed Equal Rights Amendment, many Mississippians regarded the state's failure to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment as an embarrassment as Mississippi was the only state that had never done so. Thus, on March 22, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature — on a day when few legislators were even listening and with no opposition — finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment.

Marjorie Julian Spruill, Ph.D., is associate vice chancellor for institutional planning and research professor of history at Vanderbilt University. Previously she was professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi. She is the author of New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States, Oxford University Press, 1993. She has edited three books: One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, NewSage Press, 1995, Votes for Women! The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation, University of Tennessee Press, 1995, and a new edition of Mary Johnston’s 1913 pro-suffrage novel, Hagar, University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Jesse Spruill Wheeler, her son, studied Mississippi history while in the ninth grade during the 2000-2001 school year.

-

Nellie Nugent Somerville (1863 - 1952) Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

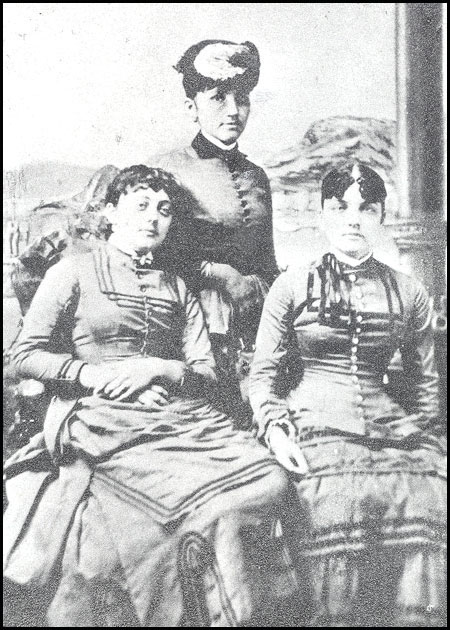

Left, Camille Bourges (Mrs. Leroy Percy), center, Lucy Robinson (Mrs. Henry P. Hawkins), right, Nellie Nugent (Mrs. Robert Somerville).Photo circa 1880. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Sources for Further Research and Reading:

Manuscript Collections:

- Somerville-Howorth Family Papers, Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Some of these materials are available on microfilm in the Nellie Nugent Somerville Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.

- Belle Kearney Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.

Theses, Articles, and Books:

- A. Elizabeth Taylor, “The Woman Suffrage Movement in Mississippi, 1890-1920,” Journal of Mississippi History 30 (February 1968):1-34.

- Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Anne Firor Scott, “Nellie Nugent Somerville,” in Notable American Women: The Modern Period by Barbara Sicherman and Carol Hurd Green, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, pp. 654-56.

- Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, “Belle Kearney,”in American National Biography, John A. Garraty, editor, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Mary Louise Meredith, “The Mississippi Woman's Rights Movement, 1889-1923: The Leadership of Nellie Nugent Somerville and Greenville in Suffrage Reform,” M.A. Thesis, Delta State University, 1974.

- Nancy Carol Tipton, “It is My Duty: The Public Career of Belle Kearney.” M.A. Thesis, University of Mississippi, 1975.

- Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, editor, One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, NewSage Press, 1995.

- Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, editor, Votes for Women! The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation, University of Tennessee Press Press, 1995.