Burnita Shelton was one of six children, and the only daughter, born on December 28, 1894, to Burnell Shelton and Lora Drew (Barlow) Shelton. She was part of an educated, civic-minded family. Her mother was a graduate of Whitworth College, a boarding school for young women in Brookhaven, Mississippi, and her father was a planter, cattleman, and also an elected official serving at various times as sheriff and tax collector of Copiah County and as the clerk of the chancery court.

A passion for law

From a young age, Burnita Shelton accompanied her father along the campaign trail and to the courthouse where he worked. Unsurprisingly, she announced to her family that she felt at home in the courthouse and wanted to pursue a legal career. Her father, however, pushed her toward the study and teaching of music which he believed was a more ladylike profession. In 1915, he sent her to the prestigious Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, where she received a teaching certificate. However, she was never dissuaded from her ultimate dream to become a lawyer. While studying for her teaching certificate in Ohio, she wrote to her relatives and asked that they send her law books to read. Hoping to discourage her, they sent her the most boring books they could find. Their efforts failed.

Against her family’s wishes, Burnita married Percy A. Matthews in 1917, a young man she had known in high school. Percy was planning to join the U. S. war effort in World War I. Almost immediately after the marriage, he enlisted and left to fight in Europe as a pilot. Burnita Shelton Matthews then lived independently, supporting herself by teaching music in a small town in Georgia. However, she later moved to Washington, D. C. to work with the Veterans Administration. She purposely chose to live in the nation’s capital because it held three of the very few law schools that would accept women at the time. When her father learned of her plans to enroll, he offered to pay for her law school tuition. She rejected his offer, and instead, worked during the day to put herself through National University Law School at night. Matthews graduated with an LL.B. (Bachelor of Laws) degree in 1919 and L.L.M. (Master of Laws) and Master of Patent Law degrees in 1920.

National Woman’s Party

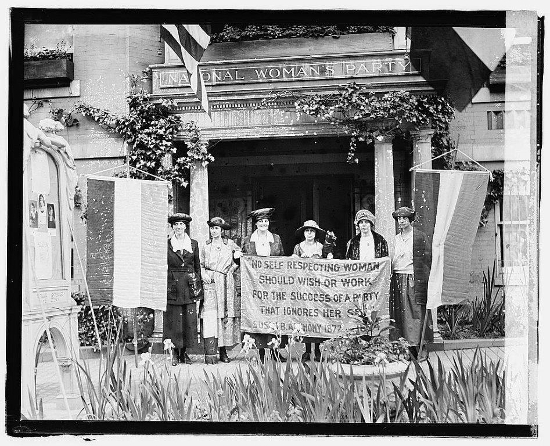

While in law school, Matthews became involved with the National Woman’s Party (NWP), a women’s suffrage organization formed in 1916 following a split with the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, the main women’s suffragist organization in the nation at the time. The NWP, led by Alice Paul, preferred the use of more direct and forceful tactics to achieve passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, including picketing and protesting by women holding large cloth banners emblazoned with suffragette messages.

Although her NWP activities were limited to weekend picketing at the White House, Matthews continued to work with the NWP after the amendment’s passage and her graduation from law school. Throughout the 1920s, she headed up the NWP’s Legal Research Department. This department engaged in a decade-long project of identifying legal discriminations against women throughout various state laws. Consequently, states passed several pieces of legislation drafted by Matthews, which helped to remove the disqualification of women as jurors in the District of Columbia, eliminate the preference of men over women within the laws governing the right to inherit property and wealth in Arkansas, the District of Columbia, and New York, gave female teachers in Maryland and New Jersey equal pay with men teachers for equal work and allowed married women in South Carolina to sue and be sued without their husband’s permission. During this time, Matthews also assisted Alice Paul, head of the NWP, in creating the original version of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which sought to remove all legal distinctions between men and women in the U. S. Constitution, and she became actively engaged in the organization’s effort to secure passage of the ERA. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Matthews served as the legal expert for the NWP and as the organization’s spokesperson giving a total of eight testimonies before Congress in support of the amendment. Although the ERA was never passed, its proposal helped to change the national conversation concerning the meaning of gender equality.

Matthews also served as legal counsel for the NWP in a dispute with the federal government when it attempted to acquire ownership of the NWP’s headquarters and land as the ideal site for a new U. S. Supreme Court building. During the trial which ultimately decided the matter, Matthews was able to produce evidence which showed that the federal government’s monetary offer to compensate the NWP for title to the property was significantly less than the property was worth given its historical significance. The jury awarded the NWP approximately $300,000, which at the time was the largest condemnation award ever made by the federal government.

Branching out

Matthews’s success against the government in this case cemented her reputation as one of the best lawyers in Washington, and consequently, her private practice also grew. She eventually joined two other female lawyers with ties to the NWP, Rebekah Greathouse and Laura Berrien, in the creation of the firm, Matthews, Berrien, and Greathouse. As her affiliation with the NWP receded during the late 1930s and 1940s, Matthews’s activities shifted from working with individual clients toward work with legal and professional organizations, such as the District of Columbia Bar Association, Woman’s Bar Association, American Bar Association, and National Association of Woman Lawyers. She also taught at the Washington College of Law, which later became part of American University.

First female federal trial court judge

In 1949, President Harry Truman appointed Matthews to the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia. She became the first woman ever appointed to a federal trial court and only the second woman ever appointed to a federal constitutional court. As a federal judge, she hired only female law clerks and bluntly counseled them against having children if they intended a career in law. Judge Matthews herself did not have children, and until her husband’s retirement in 1955, she never actually lived with him for any length.

During her twenty-eight year tenure on the bench, Judge Matthews presided over several major trials. In 1955 and the beginning of the civil rights movement, she refused to order the State Department to issue a passport to the African American actor and political activist, Paul Robeson, ruling that he had first to exhaust all administrative remedies. In 1957, she presided over Jimmy Hoffa’s trial for bribery. At the time, Hoffa was president of the Teamsters Union, which originally represented freight carriers and warehouse workers, but today, represents many different occupations. While the Hoffa trial was quite difficult with many attempts made to disrupt it, Judge Matthews maintained control of her courtroom, and Hoffa was eventually acquitted. In the case of Fulwood v. Clemmer in 1962, she upheld the right of Black Muslims, also known as the Nation of Islam, to conduct religious services in the local prison. In this case, a local minister testified that he did not view Black Muslims as part of a legitimate religion, but Matthews rejected this claim. In another case, she ruled that the local prison had to reduce, though not eliminate, the use of pork in its meals to accommodate the religious beliefs of Muslims, who are forbidden from eating pork by the tenets of Islam. In 1969, Judge Matthews became senior judge and heard cases in both the U. S. District Court and the U. S. Court of Appeals (by designation) until her retirement in 1977.

Final return to Mississippi

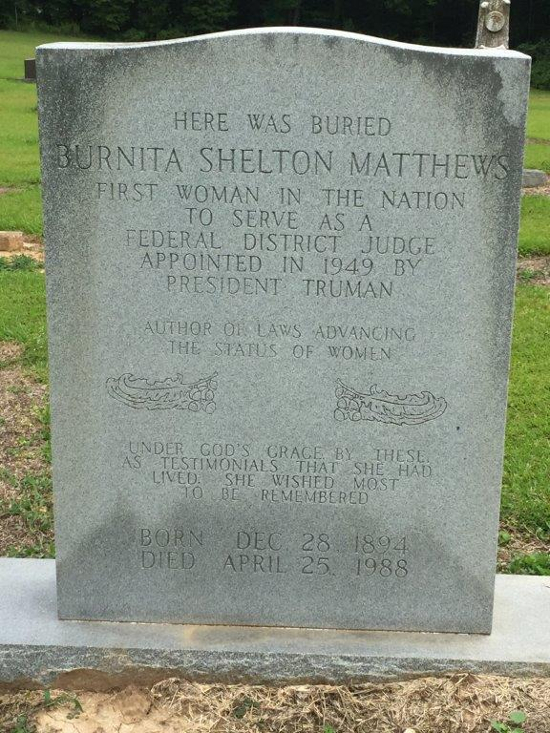

Seventy years after leaving Mississippi to pursue her legal career, Burnita Shelton Matthews returned to her home state for the last time. She died due to a stroke in 1988 and was buried in the Shelton Family Cemetery in Copiah County, Mississippi. Her headstone notes that Burnita wanted to be remembered for two things: the first woman to become a U. S. district court judge and the “author of laws advancing the status of women.” As a lawyer, suffragist, feminist, and judge, Judge Matthews was truly a pioneer for all women.

Kathanne (“Kate”) W. Greene is an associate professor of political science at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Other Mississippi History Now articles:

Equal Rights Amendment and Mississippi

Mississippi Women and the Woman Suffrage Amendment

Lesson Plan

-

Photograph of young Burnita Shelton Matthews in Washington, D.C. in 1925. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Reference URL https://www.loc.gov/resource/mnwp.275007/. -

Photograph of women suffragists picketing in front of the White House in 1917 for the right to vote. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Call No. LC-USZ62-31799, Reference URL http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97500299/.

-

Photograph of a group of young members of the National Woman's Party before the Capitol in 1923 as they sought to meet with the senators and congressmen from their respective states to ask them to vote for the Equal Rights Amendment. In the foreground is Anita Pollitzer, secretary of the National Woman's Party. Left to right: Blanche Alsop, Virginia; Heath Jones, Delaware; Maud Younger, California, legislative chairman of the National Woman's Party; Legare Obear, Georgia; Burnita Shelton Matthews, Mississippi; Anne Archbold, Maine; Wilma Henderson, Massachusetts; Emma Brown, Maryland; Rowena Dashwood Graves, Colorado. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Reference URL https://www.loc.gov/resource/mnwp.160003 /. -

Photograph taken on June 2, 1920, of the officers of the National Woman’s Party in front of the Washington Headquarters before leaving for the Chicago Convention to take charge of the suffrage effort in the Convention of the Republican Party. Left to right: Sue White, Benigna Green Kalb, Jas Rector, Mary Dubrow, Alice Paul, and Elizabeth Kalb. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Call No. LC-F8-8181, Reference URL https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/npc2007001704 /. -

Photograph taken in 1929 of U.S. Attorney General William D. Mitchell presenting a check to Burnita Shelton Matthews, attorney for the National Woman's Party, as payment for the National Woman's Party Headquarters located at 21 First Street, Northeast, Washington, D.C. The location was used as the site for the U.S. Capitol from 1815 to 1819 but was torn down following this sale to accommodate the new location of the U.S. Supreme Court Building. On the left is Maud Younger, congressional chairman of the National Woman's Party. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Reference URL https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000324/. -

Photograph of Judge Burnita Shelton Matthews. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Photograph of the headstone at the gravesite of Burnita Shelton Matthews located in the Shelton Cemetery in Copiah County, Mississippi. Courtesy of Kate Greene.

Sources and suggested readings:

Burnita Shelton Matthews Collection, Schlesinger Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Mississippi Department of History and Archives, Jackson, Mississippi.

Greene, Kate. “Burnita Shelton Matthews: The Struggle for Women’s Rights.” In Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, edited by Martha H. Swain, Elizabeth Anne Payne, and Marjorie Julian Spruill, 144-159. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003.

“Torts over Tempo: The Life and Career of Judge Burnita Shelton Matthews,” Journal of Mississippi History, 56, no. 3 (August 1994): 181-210.

Matthews, Burnita Shelton. “Burnita Shelton Matthews: Pathfinder in the Legal Aspects of Women.” Interview by Amelia R. Fry, Washington, D.C., April 29, 1973. Suffragists Oral History Project, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Obituary of Burnita Shelton Matthews. The New York Times, April 28, 1988.