“Southern blacks not only out-sang, out-marched, and out-prayed their oppressors, but they also out-thought them.”

Adam Fairclough, historian

Opening curtain

What follows is an interpretive overview of a high moral drama played out in the public spaces of a Deep South state. Elsewhere in this online publication, historians have explored the role of violence and nonviolence and the role of youth in Mississippi’s Black freedom struggle. The focus shifts here to the logic and the purpose behind civil rights activism in Mississippi from 1963 to 1965, and explains how Black activists and their few white allies broke the back of Jim Crow by compelling a reluctant federal government to enforce the Constitution. These years might be called the movement’s street theater period.

The scene: a defiant state

Civil rights activists such as as Fannie Lou Hamer, the Ruleville sharecropper who became one of the American heroes of human rights, often said that if the Civil Rights Movement could “crack Mississippi” it could “crack the entire South.” The state was, by all accounts, the toughest stop on the color line.

Beginning in the mid-1940s after World War II and accelerating after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, there were signs of modest change elsewhere in the South. But not in Mississippi. In the mid-1960s the state still seemed frozen in a 19th-century mold. The state’s schools remained racially segregated. Not one in ten Black adults was registered to vote. Those who would challenge this way of life were confronted by the full power of the state, whether exercised by public officeholders, judges and juries, or law enforcement officers. There were White dissenters — a courageous few newspaper editors, some conscience-stricken clergy, a small handful of college professors, and other social critics. But their voices were scarcely audible in an otherwise closed society most notable for its racial repression and its fear of change.

Setting the stage

The roots of the Black freedom struggle can be found deep in the soil of the nation’s colonial experience. The modern Civil Rights Movement, however, is a mid-20th century development. Some historians trace it to the return of Black soldiers after World War II. Others find its origins in the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycotts in 1955 and 1956, or in the Brown decision. Some point to the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till as the moment when the movement first coalesced in Mississippi. But whatever its date of origin, the civil rights struggle in Mississippi had accomplished little by the end of the 1950s.

On the national scene a new decade brought some hopeful but ultimately ineffectual developments: the Civil Rights Act of 1960 (scarcely an improvement on the weak Civil Rights Act of 1957) and some promising rhetoric from a young Democratic president, John F. Kennedy. But by 1963 nearly a decade of nonviolent direct action campaigns such as school desegregation petitions, voter registration drives, consumer boycotts, public library “read-ins,” and lunch counter “sit-ins” had only brought a reign of white terror and economic repression. Their heads bloodied and their early optimism shattered during the first stage of nonviolent protest, growing numbers of civil rights activists in the state concluded that white supremacist hearts and minds could not be moved by passive resistance and direct action campaigns. They had learned the hard way that even the most heroic acts of direct action could not produce what Martin Luther King Jr. had wistfully called a “redemptive” and “beloved community” of racial equality. Increasingly civil rights activists across the country came to recognize that real progress toward equal rights could only come through massive federal intervention, that only a second federal Reconstruction could complete the act of emancipation and redeem the promise of the Constitution.

The method

But how? How to awaken the nation’s conscience? How to inspire a new Reconstruction? Neither objective seemed within reach. Southern segregationists exercised enormous power in both the U. S. Congress and the national Democratic Party. Apathetic northern White people often viewed the “Negro problem” as a “southern problem.” The federal system, in both custom and law, generally left human rights to the uncertain protections of state government.

These vexing questions and obstacles inspired creative movement strategies across the South. The example of King’s crusades in Alabama illustrates the challenges confronting civil rights workers everywhere and help explain parallel developments in Mississippi. Project C – Project Confrontation – scripted by Southern Christian Leadership Conference strategists for King’s 1963 Birmingham Campaign was not an exercise in idealism. Project C, as its name implied, was calculated to provoke an excessive show of white force in Birmingham that would unsettle the national conscience and force federal intervention. Critics said that it deliberately excited White violence. More sympathetic observers understood that it was designed to create a controlled disorder in which routine police brutality against Black citizens could be documented by the news media.

The plan required a high degree of unwitting cooperation by Birmingham Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor and his heavy-handed cops. Connor did cooperate, playing the role of a hardhearted “heavy” as though he had read the script. As the great moral drama that was the Birmingham Campaign unfolded, the press came from around the world, and public opinion, at home and abroad, was shaped by some of the most searing images of an American scene ever captured on film: nightstick wielding officers, police dogs, and high-pressure water hoses deployed against singing, marching, praying African Americans, a great many of them children.

The Birmingham Campaign alone did not produce the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But no one should doubt that the weight of King’s demonstrations, combined with the 1961 Freedom Rides, the 1962 University of Mississippi integration crisis, and the broader southern struggle for suffrage and desegregation pushed the politically cautious Kennedy administration to introduce the sweeping legislation that President Lyndon Johnson later signed into law in 1964.

And King’s high-voltage Birmingham morality play was masterfully reproduced in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 where the segregationist power structure once again allowed itself to be played, as one unnerved local official admitted, “like a violin.” The Selma Campaign, combined with parallel events elsewhere — most notably Mississippi’s “Freedom Summer” campaign of 1964 — brought national outrage and government action. Congress enacted and President Johnson signed one of the most effective laws in American history, the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The theater

Meanwhile, Mississippi activists were staging their own well-documented dramas of national exposure. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activists, often working in concert with a larger coalition of Mississippi civil rights workers in the Council of Federated Organizations, or COFO, shifted course in 1963. They planned to expose, for all the world to see, the gap between American principles and Mississippi practices.

The first major production in this new Mississippi theater of realism was the “Freedom Election,” a separate “mock election” timed to coincide with the state’s gubernatorial election of 1963. COFO’s “nominee,” Aaron Henry, a Clarksdale pharmacist and state NAACP leader, and his slate of “Freedom Candidates,” didn’t really have a prayer. In a state where nearly all African Americans were disfranchised, they were “elected” in an unofficial straw ballot by some 80,000 citizens who could not legally vote. They were victorious, however, in the theater of national opinion, having demonstrated that, as Robert Moses, SNCC’s most charismatic field worker, put it, “if Negroes had the right to vote without fear of physical violence and other reprisals, they would do so.”

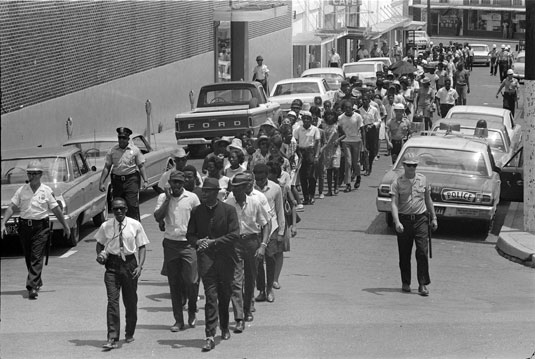

More dramatic examples of injustice and discrimination in Mississippi were held up to public view during Freedom Summer. COFO’s “Summer Project” brought in some 700 White northern student volunteers to help focus the nation’s attention on Mississippi. The volunteers were children of the middle class, from good colleges and influential families. White officials in Mississippi warned of an “invasion” by “beatniks” and “communists.” Cynics, including some in the U. S. Department of Justice, alleged that COFO planned to get “some white kids hurt [so] the country would be up in arms.” Civil rights leaders, in fact, took every reasonable precaution, but they knew that they could not protect the volunteers from White terrorism.

The Summer Project played in twenty-five communities in twenty Mississippi counties. It brought 17,000 Black voter applicants to courthouses across the state, nearly all of whom were denied registration. It was also remarkable for its Freedom Schools for Black children, its mass meetings in Black churches, its street demonstrations, and voter registration marches. Not least, the Summer Project led to the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as the principal vehicle for Black voter education and, ultimately, electoral participation. The Project attracted the world’s attention early when three civil rights workers were murdered by some Ku Klux Klan members near Philadelphia, Mississippi, even before many of the volunteers arrived. This savage act was followed by others scarcely less riveting. The toll by summer’s end included thirty-seven burned out Black churches, eighty volunteers beaten, and scores of Blacks arrested for demanding their rights as American citizens.

Freedom Summer as street theater was a stunning achievement. Its successes could be counted not in lunch counters desegregated or in Black voters registered, but in media impact. Easily the most sustained production in modern civil rights history, it provided summer-long, national and international exposure of the evils of Jim Crow in the deepest of the Deep South states. Fannie Lou Hamer pronounced it “one of the greatest things that ever happened in Mississippi.”

Two final examples of this Mississippi theater of public exposure followed in the wake of Freedom Summer. Late in the summer, having been excluded from the all-White caucuses of the all-White Mississippi Democratic Party, the MFDP sent a slate of delegates to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Although the “freedom delegates” were not seated, and the MFDP did not win the convention’s recognition as the “official” state Democratic Party, the Mississippi Movement won the opportunity to tell its story before a national television audience.

In January 1965, the MFDP found yet another national stage, this one in the nation’s Capitol, where it challenged the electoral legitimacy of Mississippi’s five congressmen and urged the seating of three Black winners of a second Freedom Election. Again there was victory in defeat. Congress seated the all-White congressional delegation, but not before the MFDP presented the House of Representatives with 10,000 pages of testimony from 600 witnesses on voter discrimination in Mississippi. If this was not precisely street theater, it was theater nonetheless — and it was performed, in this instance, within the very corridors of federal power.

The final act?

A few months later, the revolutionary Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law. Under the provisions of that measure, the Justice Department dispatched federal registrars to Mississippi courthouses and Black voter registration soared. Within a year half of all eligible Black Mississippians were registered to vote. Within a few years, the state with the nation’s highest percentage in Black population could boast of more elected Black officials than any other state. To no one’s surprise, as Black candidates sought and won office and White candidates found it useful to openly woo Black voters, the explicit, point-blank race baiting that for so long had been the staple of Mississippi political campaigns all but disappeared.

Race problems endure, of course, in Mississippi and throughout the nation. Politics remain deeply polarized by color, ethnicity, and religion. Ancient traditions largely of a racial nature still haunt public and private life.

A Mississippi governor, the late Kirk Fordice, may have boasted that “Mississippi does not do race,” but in fact, many Mississippians, both Black and White, still do. Yet enormous change has flowed in the wake of Jim Crow’s collapse. The new Mississippi is dramatically different from the old Mississippi. That difference can be traced, in substantial part, to the street theater in the mid-20th century when Black Mississippians played Jim Crow’s bullies like a violin, not only out-singing, out-praying, and out-marching their segregationist oppressors, but out-smarting them too.

Neil R. McMillen, Ph.D., professor emeritus of history, University of Southern Mississippi, is the author of several books, including Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow.

Lesson Plan

-

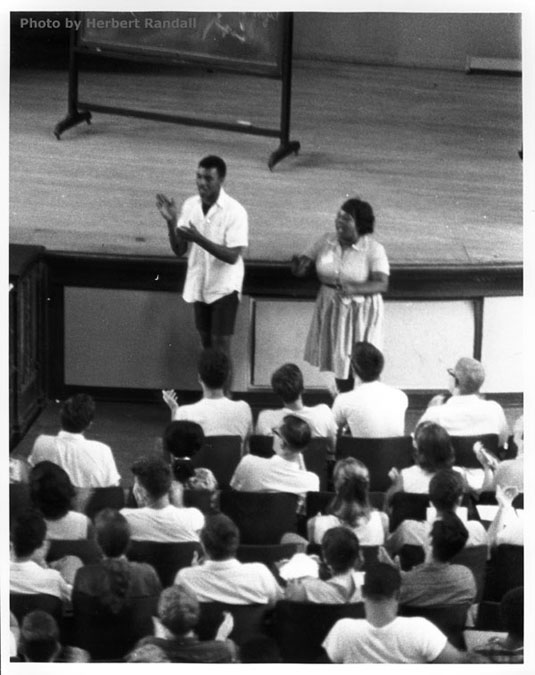

SNCC staff leads volunteers in freedom songs during the second 1964 SNCC Orientation Session at Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio. In the front of the audience, right, is Fannie Lou Hamer and, left, SNCC staff member Chuck Neblett. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

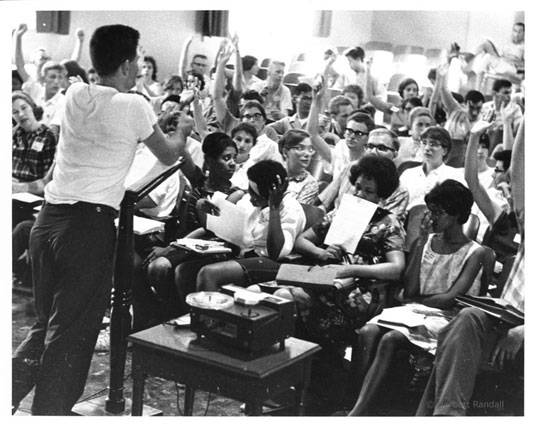

Dr. Staughton Lynd, director of the Mississippi Freedom Schools, instructs Freedom School teachers during the second 1964 SNCC Orientation Session. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.

-

Freedom Summer volunteers arrive at COFO Headquarters in Hattiesburg in June 1964. COFO's "Summer Project" brought in some 700 white northern student volunteers to Mississippi. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

Civil rights activists meet outside Freedom Summer headquarters in Hattiesburg. Left to right: Reverend W. D. Ridgeway; SNCC Field Secretary Sandy Leigh; and Carolyn Reese, school teacher from Detroit, Michigan, and co-coordinator of the Hattiesburg project’s Freedom Schools. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

A civil rights march in downtown Hattiesburg. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1994.0005/Box 161, Folder 1. -

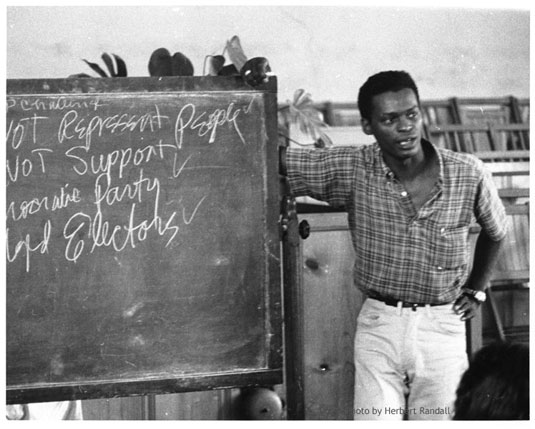

Sandy Leigh, SNCC Field Secretary, makes a presentation on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to Freedom School students. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

Fannie Lou Hamer. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-U9-12470B-17

Selected bibliography

Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Fairclough, Adam. To Redeem the South of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King. Athens, Ga: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

McMillen, Neil R. “Black Enfranchisement in Mississippi,” Journal of Southern History (August, 1977).

Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: Dutton, 1993.

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Sinsheimer, Joseph A. “The Freedom Vote of 1963: New Strategies of Racial Protest,” Journal of Southern History (May 1989).