“Dear Rev. Bishop,” wrote Kate Abraham of Greenwood in March 1933, “I lost everything I that I own the house which I live in caught a fire.” A member of the town’s small Syrian Catholic community, Abraham had exhausted every local option in her search for help. “I haven’t got nothing to eat and nobody help me, my husband have been dead eleven years,” she said. Abraham asked the bishop for “anything that you will do to help me,” and pled again, “me and my son is starving to death, my son have to go to school without breakfast and dinner.”

Bishop Richard Gerow forwarded Abraham’s request to her priest, who replied immediately. Abraham “has been given help by her own people, Syrians, by the Red Cross, by the R.F.C. [Reconstruction Finance Corporation], and I too have been fleeced one way or another at different times,” he wrote. Abraham had also received aid from Leflore County, petitioned the governor and a local Southern Baptist minister, and appealed to the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic society with a chapter in Greenville. “I do not say all this to cool down your charitable feelings toward this party,” explained the priest, “but to the credit of those who have been doing for her. Many people here are in difficult conditions, and I do not know that she is any worse than the others.” Kate Abraham had appealed to nearly every public and private source of relief available, and still she needed more.

Kate Abraham’s desperate plea and her priest’s defensive response illustrate the breakdown of private relief in the early years of the Great Depression. For decades, religious aid societies had claimed responsibility for helping those at the bottom of the capitalist economy. Yet even at their best, those agencies turned away many more people than they helped.

The Great Depression brought widespread suffering, and it crippled southern religious agencies at the moment people needed them most. As a result, Mississippi religious leaders joined others from across the nation to call for help from the federal government. When President Franklin Roosevelt took office, religious leaders celebrated the hand off of social programs from church to state. White clergy took credit for the New Deal, but they also fought to ensure that it upheld both White supremacy and their churches’ moral authority.

Before the Depression, Southerners generally thought about poverty as the result of individual failures, but many also worked to help the suffering. Even as they emphasized evangelism, black and white religious agencies established orphanages, hospitals, schools, and settlement houses. Women’s organizations distributed clothing and food. Some White people could access public support—a few dollars in Mothers’ Aid or a municipal poorhouse—but African Americans, ethnic minorities, and most White people turned to churches and religious agencies when they needed help. As Abraham’s pleas show, aid for the needy was scattered at best.

Then, disaster struck. In 1930, a drought scorched cotton and food crops alike. Prices for the remaining cotton dropped, and farmers prepared for a hungry winter. Then, a wave of bank failures swept the region. Even farmers who had savings, lost them.

Religious leaders struggled to respond to a crisis that no one yet understood. Many hoped for a great revival, confident that people would turn to the church in hard times, but the crisis only deepened. Some churches provided a place for people to seek comfort and to express the sorrow and pain they experienced, while others failed to acknowledge the shared pain of the Depression. Overwhelmed by need both inside and outside their doors, members struggled to keep churches open and charities running.

Private aid agencies faced several crises at once. The number of needy people soared, and donations plummeted. Many aid organizations shut down. Between 1929 and 1932, national income dropped by more than 50 percent. Wage earners’ income sank by 60 percent, and salaried workers’ income fell by 40 percent. Until 1933, church giving held steady as a proportion of national income, but that still meant a 50 percent decline in donations just as demands on church resources peaked. Churches cut charitable spending first. Even the president of the Southern Baptist Convention admitted, “We are putting off the Lord’s cause while we try to settle with our other creditors.” When the money ran out, the churches could not help. Some asked the state to intervene where they had failed.

Mississippi religious leaders cheered when Democrat Franklin Roosevelt took office as President in March of 1933 on the promise of establishing a social welfare program, “a new deal for the American people.” Roosevelt won 96 percent of Mississippi’s votes, and the state’s white Protestant leaders celebrated the New Deal’s relief and recovery programs as their own accomplishment.

White Methodist editor D.B. Raulins applauded the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which regulated workers’ hours and wages, made provisions for the right of workers to unionize, and put people to work on infrastructure projects. “It is gratifying in the highest degree,” reported Raulins, “that our government is actually attempting to try out some of these things for which the Christian church has been contending for a quarter of a century.”

Religious leaders’ enthusiasm for the New Deal grew as its programs took effect, although clergy wanted a more prominent role in distributing government relief. The relief and recovery programs of 1933, known as the first New Deal, set the stage for the more permanent programs of 1935, or the second New Deal. The new legislation included the Social Security Act, a federal retirement program that also made provisions for orphans and the disabled.

In September of 1935, Roosevelt wrote letters to the nation’s clergy to ask for their thoughts concerning the New Deal. Nearly 30,000 wrote back, and of the 12,096 clergy who responded by November, 84 percent approved. In Mississippi, 92 percent of clergy responded more positively than negatively, and only 4 percent were entirely opposed to Roosevelt’s programs. A Mississippi rabbi believed Social Security to be “drawn up in the spirit of Israel’s ancient prophets, those eloquent and fearless protagonists of social justice and righteousness.”

Black clergy responded cautiously, because White Mississippians worked hard to limit the New Deal’s programs for African Americans. One minister wrote that he supported Social Security “providing this Act is carried out with an equally divided share to all poverty stricken American citizens, regardless of race or color.” However, it was not. Even though Roosevelt prohibited explicit racial discrimination, southern Congressmen ensured that Social Security did not apply to agricultural or domestic workers, the two jobs most readily available to black southerners. While the New Deal provided many benefits to Black southerners, it granted far more benefits to White ones. Still, many White clergy complained that the New Deal threatened Jim Crow segregation because it reduced local White control over African Americans’ wages and opportunities. Black clergy fought to ensure that the New Deal benefited their members as well.

By the end of the Great Depression, most White Mississippi clergy continued to celebrate New Deal relief and works programs and trusted that they held enough moral and social authority to guide the course of the New Deal. Yet a minority of White religious leaders across the South, including Mississippi, also worried that they had abandoned their moral authority to the state, and they broke their alliance with the New Deal to become its critics instead. In the coming decades, Cold War politics, civil rights controversies, and the rise of political conservatism fueled a countermovement that both fed off of and fueled religious leaders’ anxieties about the size and scope of government.

Alison Collis Greene is an assistant professor of history at Mississippi State University and the author of No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta (Oxford University Press, 2015), from which this essay has been adapted. No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta was recently awarded the prestigious Charles S. Sydnor Award by the Southern Historical Association.

Other Mississippi History Now articles:

Depression and Hard Times in Mississippi: Letters from the William M. Colmer Papers (Letters from the William M. Colmer Papers can be directly accessed here. )

Farmers Without Land: The Plight of White Tenant Farmers and Sharecroppers

Women’s Work Relief in the Great Depression

Cooperative Farming in Mississippi

Economic Development in the 1930s: Balance Agriculture with Industry

Lesson Plan

-

A black church near Greenville, Mississippi. 1936 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-009512-E._ -

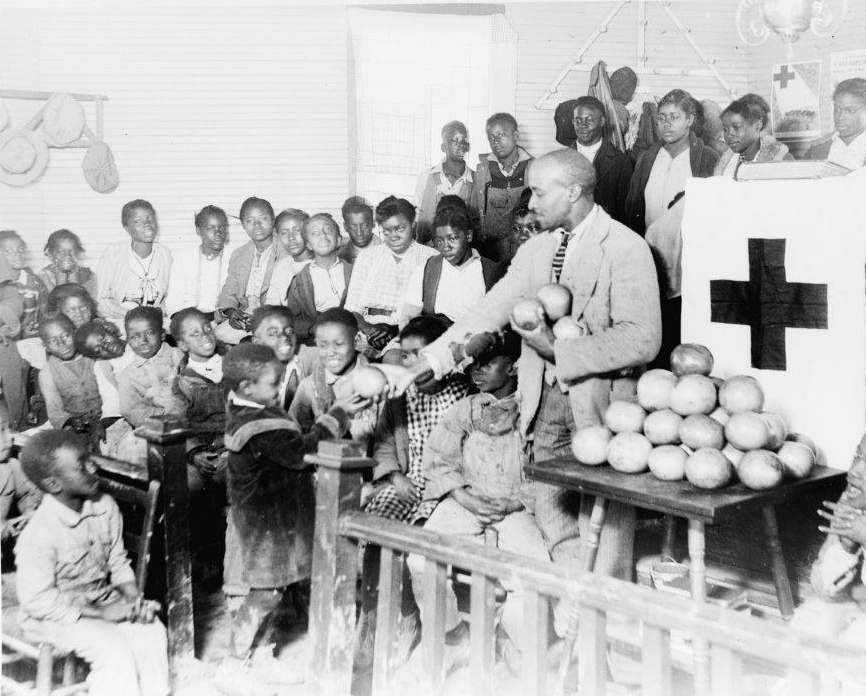

Donated grapefruit distributed in a church school near Shaw, Mississippi. 1930 or 1931 Lewis Wickes Hines photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USZ62-101908._

-

A mother and children living in an abandoned church in Laurel, Mississippi. 1939 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-DIG-fsa-8b3705 or LC-DIG-fsa-8b37053._ -

Interior of a black church in the Mississippi Delta. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017306-C._ -

Streets of Tupelo lined with Mississippians greeting President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, on their tour of Northeast Mississippi in November 1934. Courtesy of the Tennessee Valley Authority._

Sources

Butler, Anthea. Women in the Church of God in Christ: Making a Sanctified World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Greene, Alison Collis. No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Smith, Fred C. Trouble in Goshen: Plain Folk, Roosevelt, Jesus, and Marx in the Great Depression. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Sparks, Randy J. Religion in Mississippi. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001.