Three weeks before Christmas of 1903, J. R. Climer of Madison County, Mississippi, became the first resident of the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home, Beauvoir — Mississippi’s home for Confederate veterans and their wives and widows on the Mississippi Gulf Coast in Biloxi. Climer was a Tennessean by birth and a veteran of Company A of the Madison Light Artillery that fought in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at some of the most famous battles of the American Civil War. When the war began, Climer was a tombstone agent in Canton. By 1900, he had moved to the community of Flora where Climer rented a home and sold groceries. He never married, and he was not entirely sure of the year he was born. He had received some formal schooling before the war, and he was able to support himself into the twentieth century. By 1903, however, James Climer was in his late seventies (or so he thought), and he applied to enter the Confederate veteran home when word reached Canton that it would open on December 1. Delays pushed the official opening back ten days, but word of the delay did not reach Climer before he departed for the Coast. Despite the construction around him, ladies from the Biloxi chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) scrambled to make Climer comfortable when he moved in on December 2. The Jefferson Davis Soldier Home officially opened on December 10, and fifteen additional men joined Climer as its residents.

Mississippi was the second state to secede from the Union and the second-to-last state to establish a home for its aging veterans, though not from a lack of concern about veterans’ needs. Mindful of the human cost of war, Mississippi legislators began allocating funds for wounded and indigent soldiers and their families in the first years of the Civil War, and the legislature debated bills to open a state home for veterans in the 1880s. J. R. Climer’s awkward arrival at an unfinished Beauvoir, however, was representative of the difficult process of the home’s creation. Limited funds and disagreements on how to best care for veterans plagued efforts until the problem received the focused attention of the Mississippi Division of the UDC.

Constructed from 1848 until 1852, the future Confederate home was originally named “Orange Grove” by its first occupant, James Brown of Madison County, Mississippi. The property was later renamed “Beauvoir” by Sarah Ellis Dorsey when she purchased the property in the 1870s. Dorsey sold the property to Jefferson Davis in 1879. The first and only President of the Confederate States of America wrote his famous memoir, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, at Beauvoir and spent the last twelve years of his life at this beautiful, coastal location. After Davis died in 1889, his widow, Varina, and daughter, Winnie, had difficulty maintaining the property as their resources dwindled. After securing attractive writing contracts from the New York World, the women moved to New York City for Varina’s health. Following the hurricane of 1893, which severely damaged Beauvoir and many coastal communities, the preservation of the property became the cause of Mary Hunter Southworth Kimbrough of Greenwood, Mississippi, who spent summers with her husband, Judge Allan McCaskill Kimbrough, at Ashton Hall, located near Beauvoir in Biloxi. A friend of the Davises, Mary Kimbrough worked to raise funds to restore the property as “the Mount Vernon of the Confederacy.” While appreciative, Varina Davis worried that the cost of maintaining the home would always be sizable, and her health remained such that doctors did not want her living on the southern coast. Davis suggested in late 1894 that she would be willing to sell the home, and it was here that the women (it is not clear which one) launched the idea of turning Beauvoir into Mississippi’s home for aging Confederate veterans and their wives and widows.

Over the next eight years, the Mississippi UDC worked to raise the $10,000 that Davis requested for the home. This sum would provide her with adequate funds to support herself and her daughter, and it was a bargain for the state. (A hotel developer had recently offered Davis $90,000 for the property, but she refused). The UDC implemented numerous fundraising plans while battling a reluctant state legislature. Most lawmakers in the 1890s were convinced that Mississippi’s 26,728 Confederate veterans and 3,830 widows preferred to remain within their own communities and to receive pensions directly from the state.

By 1899, the UDC’s efforts were failing when Lizzie George Henderson of the J. Z. George UDC Chapter of Greenwood, Mississippi, launched a campaign to contact county clerks across the state to ascertain the number and condition of poor veterans in their areas. Henderson also wrote and sponsored trips to other state homes in order to research the costs involved with opening and running a veterans’ facility. At the 1901 reunion of the United Confederate Veterans in Memphis, Tennessee, Henderson also secured the signatures of nearly 600 veterans who clarified their desire for a state home. Although this information was formally presented to the governor and the state legislature, the plan continued to languish until the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) convinced state leaders that the home was a necessity. By 1902, however, the entire effort was on the verge of collapse once more. Tensions developed as the UDC felt that their fundraising efforts had been sidelined by the SCV, and Varina Davis’s relationship with certain UDC officers fractured over her concerns that the UDC would diminish or even erase her family’s connection to the home. Despite these concerns, the SCV finally secured the funds necessary to purchase the home. The SCV also agreed to Davis’s request that her family be forever honored at Beauvoir and that the Beauvoir UDC Chapter be allowed run it. (The latter request, however, was not fulfilled until the mid-1920s.) The UDC and SCV applauded the results of their long-fought struggle, and the UDC agreed to use the funds they raised to furnish the home and grounds. In February of 1903, the sale was finalized with the delivery of $8,000 in cash and a $2,000 promissory note. During the following year, the state took on the responsibility of funding the operation of the facility, which eventually comprised twelve barracks that held twenty-four people per building and four residents per room. The grounds also included a dining hall, chapel, hospital, and houses for servants and staff.

For the next fifty-four years, over 1,800 impoverished Confederate veterans, wives, and widows called Beauvoir home. Like similar facilities across the nation, there were occasional charges levied against the home concerning use of funds and care of the residents. However, all state investigations of these charges found them to be largely without grounds. In 1916, Governor Theodore G. Bilbo appointed Elnathan and Helen Tartt as superintendent and matron of the home. Except for one four-year gap, the Tartts continuously occupied these positions until the 1940s. (The couple often exchanged roles, with Helen sometimes serving as an independent superintendent, a rare role for a woman.) The Tartts ran the home respectfully and efficiently, setting Beauvoir apart from other veterans’ facilities in the country.

According to R. B. Rosenburg, a leading scholar on Confederate homes, veteran homes across the South were often characterized by overregulation and overbearing superintendents who treated the residents like prisoners or children. The veterans, Rosenburg argued, were trotted out for Confederate memorials and parades as though they were “living monuments” but were otherwise largely forgotten by the public. Historians James Marten and Elna Green, however, have countered this image by arguing that southern facilities fared better than their northern counterparts because Confederate veterans were linked to southern belief in the Lost Cause. The association of veterans with the Lost Cause created more public support for southern veterans even when reports surfaced of veterans drinking, arguing, gambling, cursing, and occasionally attacking a staff member or each other. Residents of veterans’ homes felt similar pressure to live up to their reputation within the Lost Cause narrative. Still, Marten argues that contemporary reports on or coming from veteran homes created, especially in the North but also in the South, “two extreme stereotypes of veterans: feeble and incapable, or drunken and irresponsible. Americans seemed to think of residents of soldiers’ homes as less than truly men, and at least some of the men trapped in these stately prisons of gratitude agreed.”

A study of the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home begun by the University of Southern Mississippi in 2014, known as the Beauvoir Veteran Project, challenged this image of unhappy residents isolated from society in poorly run facilities. The Beauvoir Veteran Project studied the home from 1903 through its closing in 1957 and traced the home’s residents from the 1850s through the twentieth century. The study supplemented the limited number of letters, diaries, or memoirs from veteran residents with census, military service, pension, and newspaper records from the period. Contrary to common perceptions of veterans’ home residents as illiterate, chronically impoverished, and isolated, the study’s findings revealed that the majority of Beauvoir’s residents were literate, raised in middle-class families, and active in the Biloxi community while living at Beauvoir. Researchers have also found that Beauvoir residents were not “trapped in . . . stately prisons.” Except for the severely ill, most veterans, wives, and widows were only temporary residents of Beauvoir. Many were “honorably discharged” when family members found the means to care for them at home. Some of these residents later returned, only to leave again, while others returned and remained and Beauvoir until their deaths. The Beauvoir Veteran Project has revealed a far more fluid and active home than historians have traditionally understood Confederate soldier facilities to be. The project has also shown that Beauvoir challenges the idea that these were traditionally all-male facilities. Mississippi’s Confederate home was one of the few to welcome female residents throughout its operation, to have a woman superintendent, and to have women (UDC members) serving on its board of directors since the 1920s.

In its prime, 250 men and women called Beauvoir home. The facility bustled with skits, readings, trips to veteran reunions, weddings of residents, and numerous social visits by local residents and dignitaries. As would be expected for a home with aging residents, Beauvoir also conducted a host of funerals. While some residents or their families requested that the bodies of their loved ones be sent home for burial, over 700 veterans, wives, and widows were buried at the Beauvoir Cemetery located behind the home and barracks. On February 19, 1957, the home’s last two residents, widows Mollie Lavenia Bailey of Rosedale and Mollie Cottle of Rolling Fork, were moved to another retirement home. At that time, the state of Mississippi officially closed the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home – Beauvoir and returned the control and maintenance of the property to the SCV.

Lisa C. Foster is pursuing her master’s degree in the Department of History at the University of Southern Mississippi. Her master’s thesis analyzes Mississippi’s state and local policies for helping poor veterans and their families during and after the American Civil War.

Susannah J. Ural, Ph.D. is professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi and director of the Beauvoir Veteran Project.

Lesson Plan

-

Beauvoir, 1936. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey, James Butters, photographer, April 1936, HABS MISS, 24-BILX. V, 1-3. -

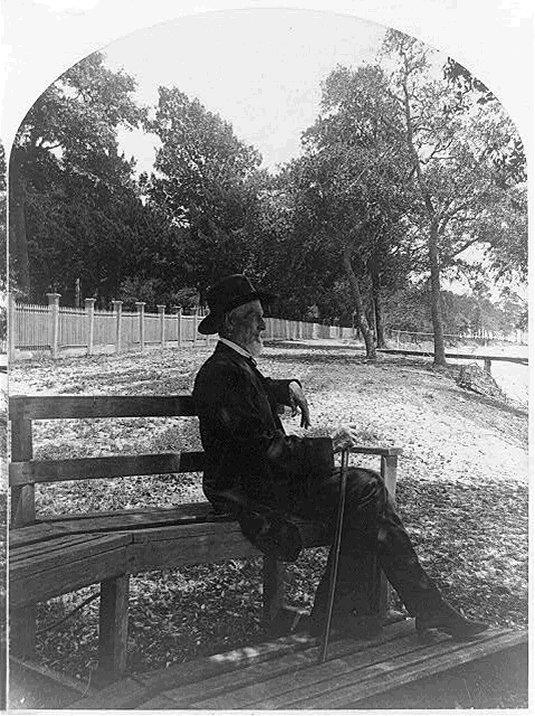

Jefferson Davis at his favorite seat looking out over the Gulf of Mexico at Beauvoir. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC- USZ62-92719.

-

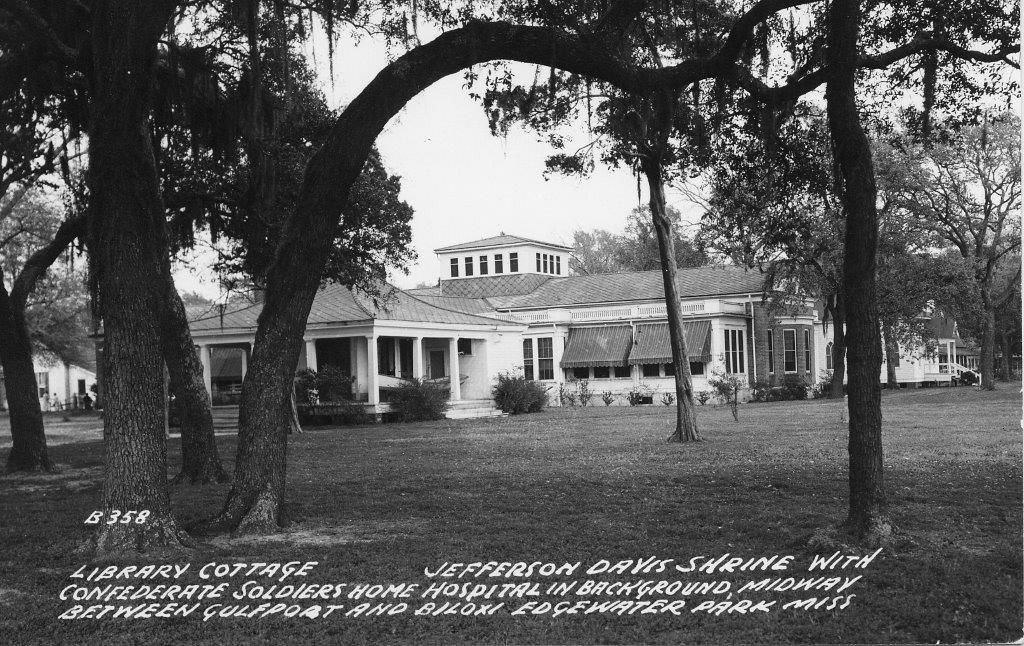

Postcard of the Beauvoir Library Cottage with the Confederate Soldiers Home Hospital in background. Courtesy of Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library, Hamill Collection. -

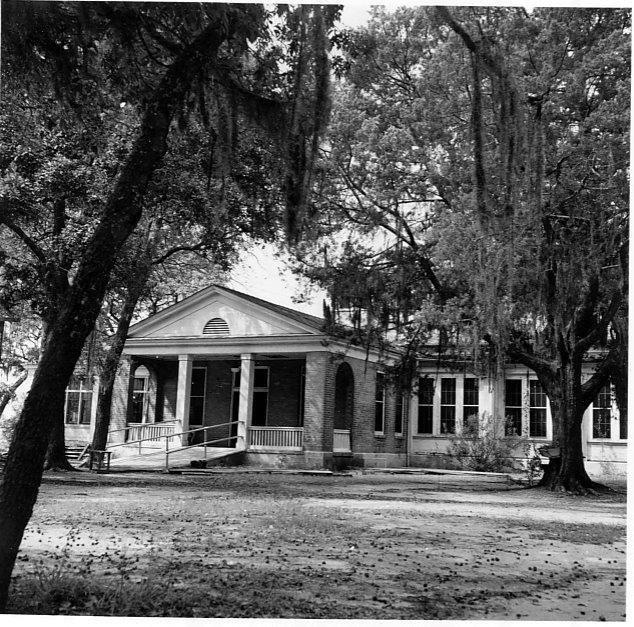

Photograph of the Confederate Soldiers Home Hospital in 1955. Courtesy of Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library, Hamill Collection. -

Photograph of the Confederate Soldiers Home Chapel in 1955. Courtesy of Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library, Hamill Collection. -

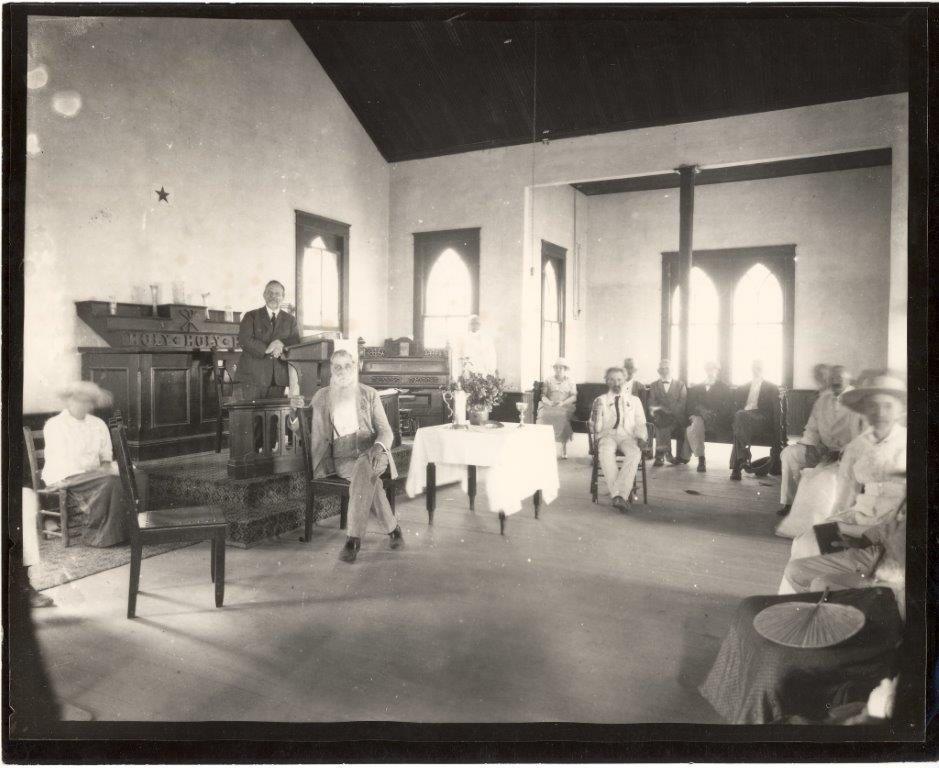

Photograph of the interior of the Confederate Soldiers Home Chapel. Courtesy of Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library, Hamill Collection.

Sources and suggested readings:

Foster, Lisa A. “A Sentimental Idea: The Jefferson Davis Beauvoir Memorial Soldiers’ Home, 1903-1957.” Honors Thesis, University of Southern Mississippi, 2008.

“The Beauvoir Veteran Project,” http://beauvoirveteranproject.org/.

Flowers, Richard R. The Chronicles of Beauvoir: The Last Home of Jefferson Davis, A History. Baltimore: Otter Bay Books, 2009.

Green, Elna C. “Protecting Confederate Soldiers and Mothers: Pensions, Gender, and the Welfare State in the U. S. South, a Case Study from Florida.” Journal of Social History 39 (Summer 2006): 1079-1104.

Marten, James. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Mass, V. B. “Jefferson Davis Dining Hall Record,” 1919-1920. http://www.lib.usm.edu/spcol/exhibitions/itemofthemonth/iomaug08.html.

Rosenburg, R. B. Living Monuments: Confederate Soldiers’ Homes in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Thompson, James West. Beauvoir: A Walk Through History. Biloxi: Beauvoir Press, 2005.

Other Mississippi History Now articles

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey: A Woman of Uncommon Mind